Packers Third Contract Risks: Green Bay’s Cautious Strategy

- The Green Bay Packers are cautious about offering third contracts to players, preferring to part ways early rather than risk declining performance.

- Recent trades, like Kenny Clark to the Cowboys, highlight the Packers third contract risks for players in their late 20s or early 30s.

- Historical examples, from David Bakhtiari to Jordy Nelson, show why third contracts often lead to regret due to injuries or performance dips.

- The Packers’ strategy of letting players go after second contracts has often proven wise, with few exceptions.

- This approach influences future decisions, like whether to extend players like Elgton Jenkins in 2027.

As a lifelong Packers fan who’s watched countless seasons unfold at Lambeau Field, I’ve seen the team navigate the tricky waters of player contracts with a mix of caution and foresight. The Green Bay Packers have a well-known philosophy: better to let a player go a year too early than a year too late.

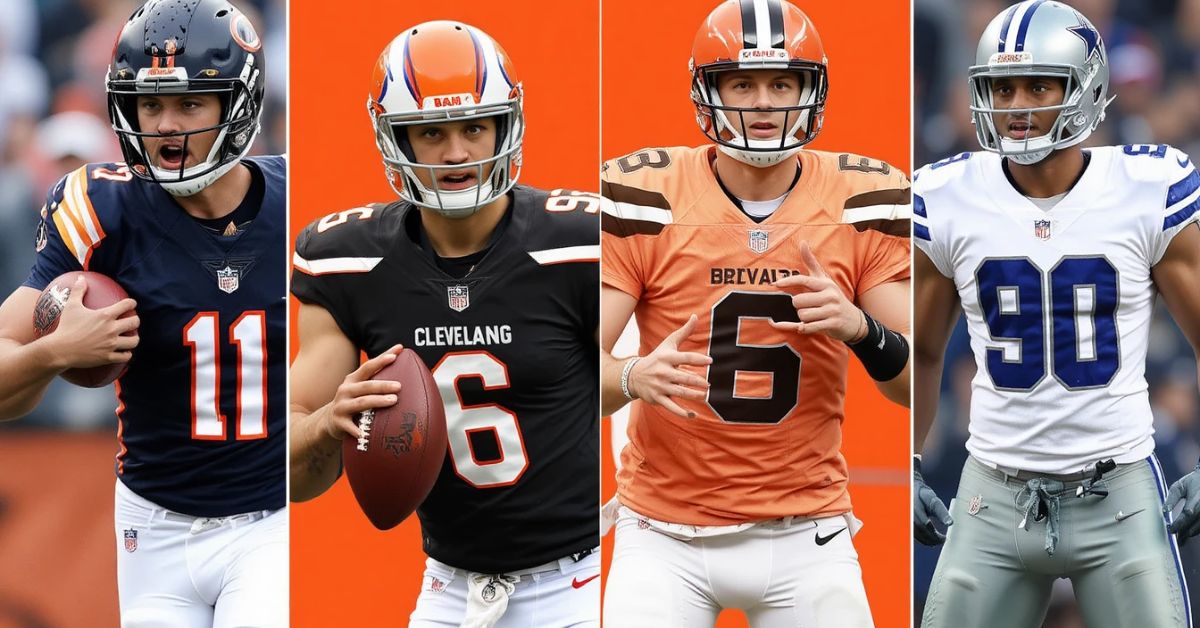

This approach, especially when it comes to Packers third contract risks, has sparked plenty of debate among fans and analysts alike. The recent trade of Kenny Clark to the Dallas Cowboys as part of the Micah Parsons deal is a perfect case study in why the Packers are so wary of these long-term commitments. Let’s dive into why this strategy makes sense, explore some notable examples, and consider what it means for the team’s future.

The Packers Third Contract Risks: Why Green Bay Treads Carefully

Offering a third contract to a player—especially one entering their late 20s or early 30s—comes with significant risks. The NFL is a brutal sport, and even the most durable players can see their performance drop due to age, injuries, or the natural wear and tear of a long career. For the Packers, who pride themselves on building through the draft and developing talent, tying up salary cap space in a declining veteran can hinder their ability to stay competitive.

The Kenny Clark trade is a prime example. In 2024, the Packers signed Clark, a stalwart defensive tackle, to a three-year extension, only to trade him a year later. The move left Green Bay with about $35 million in dead money—a tough pill to swallow. However, the trade was a necessary piece of the puzzle to acquire Micah Parsons, a generational talent. According to Packers GM Brian Gutekunst and Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, Dallas insisted on an experienced run-stopper like Clark to make the deal work. While the trade itself was a strategic win, Clark’s extension was a misstep. His 2024 season was his worst yet, hampered by a lingering toe injury, and his play in recent years hadn’t quite matched his earlier elite form.

This isn’t just a Green Bay problem. Teams across the NFL often get burned by long-term deals for aging players. The Packers’ cautious approach stems from a history of mixed results when they’ve taken the plunge on third contracts.

A Checkered History: Third Contracts That Didn’t Pan Out

Looking back at the Packers’ track record with third contracts reads like a cautionary tale. Here are some notable examples:

- David Bakhtiari: A fan favorite and elite left tackle, Bakhtiari’s career was derailed by a devastating knee injury after signing a lucrative extension. The injury effectively ended his time in Green Bay, leaving the team with a hefty contract and no on-field production.

- Jordy Nelson: After signing a new deal in 2015, Nelson tore his ACL, returned for one solid season in 2016, then struggled through an injury-plagued 2017. The Packers cut him in 2018, a year before his contract expired.

- Preston Smith: Smith signed a four-year extension in 2022, his third career contract. By mid-2024, the Packers traded him to Pittsburgh in what amounted to a salary dump, as his production didn’t justify the cost.

- Jimmy Graham: Signed as a 32-year-old free agent to a three-year deal, Graham underperformed and was cut after two seasons. Fans still wince at how little impact he had in Green Bay.

- De’Vondre Campbell: After an All-Pro season, Campbell earned a multi-year extension, but his performance never again reached that peak, making the deal a disappointment.

On the flip side, Rasul Douglas stands out as a rare success. Signed to a three-year deal after exceeding expectations as a low-profile pickup, Douglas maintained his high level of play. The Packers traded him in 2023, along with a fifth-round pick, for a third-rounder—a savvy move that recouped value when the season was faltering.

What’s striking is that none of these players finished out their third contracts in Green Bay. Injuries, declining performance, or strategic trades cut each deal short.

Read more: Green Bay Packers vs Jared Goff: Micah Parsons Threatens Lions in Week 1

When Letting Go Pays Off

The Packers’ reluctance to offer third contracts extends to their decisions to let players walk after their second deals. More often than not, this strategy has been vindicated:

- Corey Linsley: A standout center, Linsley played well for one season with the Chargers after leaving Green Bay in 2021 but declined sharply in year two and retired after playing just three games in 2023.

- Dean Lowry: After a lackluster second contract with Green Bay, Lowry was let go in 2022. His stints with the Vikings and Steelers showed little impact, proving the Packers right.

- Bryan Bulaga: Plagued by injuries in Green Bay, Bulaga played just 11 more NFL games with the Chargers after leaving in 2020.

- Randall Cobb: Cobb found moderate success in Dallas after leaving Green Bay but never recaptured his peak form. His return to the Packers later, at Aaron Rodgers’ request, didn’t change the narrative.

- Clay Matthews: After departing Green Bay, Matthews had a quiet final season with the Rams in 2019 before retiring.

These examples show that letting players go after their second contracts often saves the Packers from overpaying for diminishing returns.

The Bigger Picture: A Smart Strategy With Room for Exceptions

The Packers’ approach isn’t about being cold-hearted—it’s about staying competitive in a salary-cap-driven league. Injuries, like those to Bakhtiari and Nelson, are unpredictable, and no one can fault the team for bad luck. But the pattern is clear: third contracts rarely deliver the value expected. Green Bay has mitigated some of these Packers third contract risks by structuring contracts to minimize long-term damage and by turning failed deals into draft picks, as seen with Douglas and others.

Looking ahead, this philosophy will likely influence decisions about players like Elgton Jenkins, who’s set to hit free agency in 2027 at age 32. Jenkins has been a versatile and reliable offensive lineman, but the Packers will weigh his value against the risks of age-related decline. As of 2025, the NFL’s salary cap is projected to rise to around $282 million, per OverTheCap, giving teams more flexibility. Still, Green Bay’s front office will likely stick to their disciplined approach, prioritizing younger talent and draft capital.

Conclusion: Balancing Loyalty and Longevity

As a Packers fan, it’s tough to see homegrown stars like Kenny Clark or Corey Linsley leave, but the team’s cautious stance on Packers third contract risks makes sense. Watching players age out of their prime or battle injuries after signing big deals is a reminder that the NFL is a business, not a sentimental reunion.

The Packers’ strategy isn’t perfect—sometimes you lose a gem like Linsley for a year of brilliance elsewhere—but it’s kept them in contention year after year. For fans, it’s a bittersweet reality: rooting for players we love while trusting the front office to make tough calls that keep the green and gold flying high.

Hi, I’m Aliha! I’ve been a huge NFL fan for as long as I can remember, and I love sharing my thoughts, updates, and insights about the game. Whether it’s big plays, team news, or behind-the-scenes stories, writing about the NFL gives me a chance to connect with fellow fans who share the same passion for football.

3 thoughts on “Packers Third Contract Risks: Green Bay’s Cautious Strategy”